This is a special feature that has been produced or updated for National Health Center Week (NHCW). NHCW brings awareness to the various challenges health centers and their patients face and recognizes that patient health starts at the heart of their communities.

For more than 40 years, agricultural workers have looked to Community Health Centers (CHCs) to fulfill their primary health care needs. Health Centers serve approximately 2.5 to 3 million agricultural patients in the US.¹ Although CHCs do their best, it is still a challenge to serve rural patients due to barriers to health access. Some of these barriers include;

- Poverty

- Frequent mobility and travel

- Limited means of transportation

- Lack of time efficient healthcare delivery methods

- Cost of healthcare too expensive

- Needed services are not offered

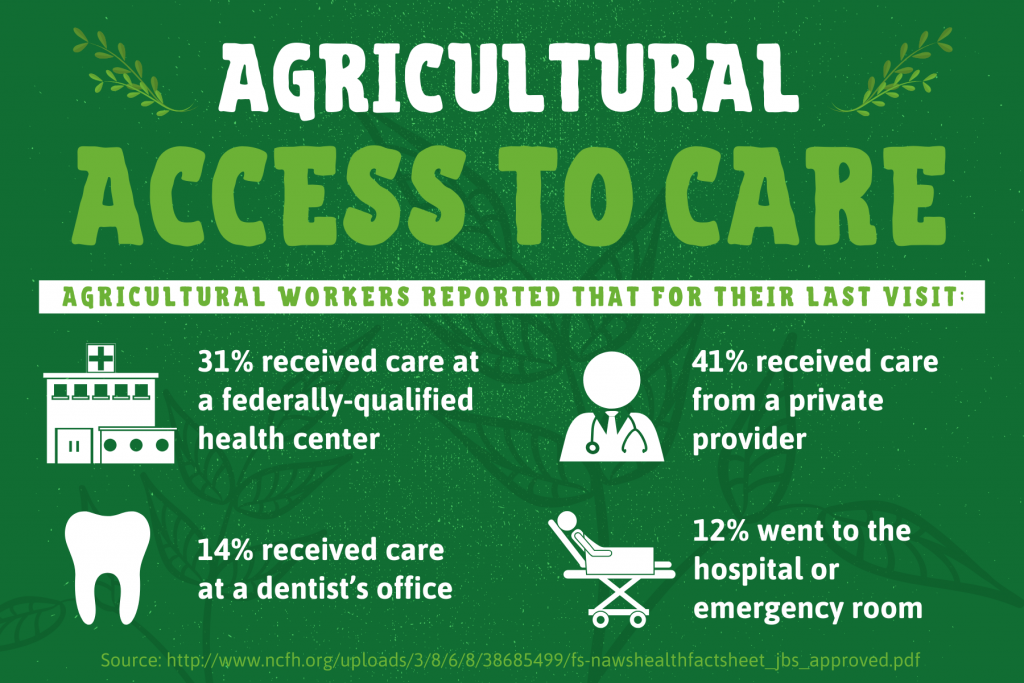

These challenges often times lead to agricultural workers seeking care in unnecessary emergency visits or having to find quality health care on their own.¹

Often, the care a rural patient needs can be treated by a Community Health Center or a Federally Qualified Health Center (FQHC). According to a study done by the National Center for Farmworker Health, Inc., the top 5 health diagnoses for farmworkers are;

- Overweight/obesity

- Hypertension

- Diabetes mellitus

- Otitis media & eustachian tube disorders

- Depression & other mood disorders

Not one of these health conditions require hospital or emergency visits.¹

FAST FACTS:

Social determinants of health account for additional barriers to care. It is good practice for providers to be cognizant of the following when dealing with a patient population that includes agricultural workers:

- 73 percent of all agricultural workers were born in a foreign country¹

- This means that 65 percent of agricultural worker patients are best served in a language that is not English²

- In 2018, there were 995,232 agricultural worker patients

- 90 percent of these patients were hispanic or Latino

- 35 percent of agricultural workers were less than 18 years old.²

- 71 percent of agricultural workers earn an income below the federal poverty line²

- Many agricultural workers report living in overcrowded living spaces, sometimes of which are found in violation of housing standards.¹

- Cultural differences, especially for Latin-American indigenous people, can prevent effective care from being achieved. Indigenous people can have skewed views of U.S. clinicians and vice versa. For example, the typical rushed schedule of a U.S. clinician coupled with a language barrier, can lead a patient to ascribe ignorance and lack of support to that clinician, because it doesn’t come across that the primary care provider is helping. On the other hand, a clinician’s biases previously gathered through brief interactions with other indigenous patients or through media can lead them to believe that a patient of a certain ethnicity has a tendency to be sicker than others, or have a higher pain tolerance.³

Health and The Law

Many policy changes have been enacted in the past year regulating the working conditions of agricultural workers, which subsequently impacts their health. Understanding changing regulations will help clinicians be prepared for what might arise in their patient populations. Here are a few notable changes:

Farmworker Fair Labor Practices Act

This law went into effect on January 1 for the state of New York. Farmworkers in the state now have the right to unionize, be paid overtime after 60 hours a week and take at least one day off per week. Under federal law, agricultural workers are still exempt from overtime pay.⁴

Immigration and Nationality Act

As of January 27, due to an overturn on an injunction, it will now be harder for immigrants to enter and stay in the U.S.⁴ The language of the new law analyzes whether an immigrant will become a “public charge,” or dependent on the government for assistance, which now means receiving benefits for more than a total of 12 months in a 36 month period. The risk assessment analyzes multiple factors, including educational level (therefore language skills), health status and financial resources. The most heavily weighted negative factors include “diagnosis of a medical condition that will require extensive medical treatment or interfere with ability to work/attend school and lack of insurance or financial resources to pay for medical costs.”⁵ The National Center for Farmworker Health reports that the average level of completed education is the 8th grade¹ and that 36 percent of agricultural worker patients are uninsured.²

Chlorpyrifos Ban

In the past year, legislators in Washington, Oregon and Maryland have all considered laws that would ban the chemical chlorpyrifos, a pesticide used to treat crops. However, research has shown that pesticide can cause harm to young children and fetuses.⁴

More advocates have been coming together to develop strategies to increase these workers’ access to care.

CARE GAP: There are approximately 2.4 million agricultural workers employed on farms and ranches in the United States.⁶ These workers often travel and live in rural places where access to health care is limited. This distance hindrance and other factors continues to be a barrier in giving agricultural workers adequate access to care.

A case study done by the California Institute for Rural Studies stated that “One universal theme that emerged from interviews with providers and (agricultural) workers is that the specialists need to come to the farmworkers, not vice versa, if they are to deliver effective service.”⁷

CERTINTELL SOLUTION: Certintell can close this health care gap by providing telehealth technology and software to Community Health Centers across the nation. This software makes virtual doctor visits possible through a platform that can be accessed from any mobile device. These visits can be done from any place where there is an internet connection. With these solutions, health care access is available wherever agricultural or rural workers are.

Though means of telehealth, all the previous listed barriers to health care access would be significantly lowered. Distance, transportation and time issues would be almost completely eliminated. The cost of care for agricultural workers would also decrease due to the limit of required in-person doctor visits. Most importantly, the patient would also be able to receive their desired care. No longer would the rural patient have to seek out health care when Certintell’s telehealth technology would bring health care to the patient.

GET ACTIVE

➠ Organize a mobile or in-person health screening event or health fair. View examples from Antelope Memorial Hospital.

➠ Visit the National Center for Farmworker Health to learn about and join the Agricultural Worker 2020 Campaign. Other ways to support Agricultural workers are available on this website as well.

This article was first featured as a part of Certintell’s 2019 National Health Center Week efforts to support the awareness, advocacy and celebration of Community Health Centers during the annual weeklong event. The original content has been expanded to provide more value to the reader.

SOURCES:

¹ “Facts About Agricultural Workers.” National Center for Farmworker Health, Inc., 2018, PDF File, http://www.ncfh.org/uploads/3/8/6/8/38685499/fs-facts_about_ag_workers_2018.pdf.

² “Facts.” National Center for Farmworker Health, 2018, www.ncfh.org/fact-sheets–research.html.

³ Holmes, Seth. “The Clinical Gaze in the Practice of Migrant Health: Mexican Migrants in the United States.” Escholarship.Org, Elsevier Ltd., 2011, PDF File, escholarship.org/content/qt9v39k0pg/qt9v39k0pg.pdf?t=pkvdxj.

⁴ “Farmworker Justice Update: 1/29/2020.” Farmworker Justice, 29 Jan. 2020, www.farmworkerjustice.org/blog-post/farmworker-justice-update-1-29-2020.

⁵ “New Immigration Policy Change: ‘Public Charge’ Final Rule – What You Need to Know.” Farmworker Justice, 21 Aug. 2019, PDF File, www.farmworkerjustice.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/FJ-Public-Charge-Fact-Sheet_8.21.19.pdf.

⁶ “Who We Serve | Farmworker Justice.” 29 July 2019, www.farmworkerjustice.org/about/who-we-serve.

⁷ Mines, Ph.D., Richard, et al. “Pathways to Farmworker Health Care.” California Institute for Rural Studies, Sept. 2002, PDF File, http://www.cirsinc.org/phocadownload/CaseStudyCoachella.pdf.